On the Challenges of Documentary Practice in the Face of Climate Change and ‘Post-Truth’

- Talk Presented at ‘The Real Thing Public Forum’, Ballarat International Foto Biennale, 2023

[Transcript w/ section headings and images from Powerpoint presentation]

Good Afternoon.

I wanted to start my talk today with a question:

How do you take a photo of climate change?

Perhaps you would travel to a dried-up riverbed and take a photo. But what would this photograph show you?

I mean, it would capture an outcome of climate change. But this feels somewhat incomplete, right? If we’re talking about photographing climate change as a phenomenon, it’s not an occasional event that happens in sporadic, discrete moments. It’s happening continuously, all around us, often going unnoticed in the present moment. It’s an event that is temporally and spatially spread in a way that often escapes our senses, and in this it challenges the very limits of photographic documentation.

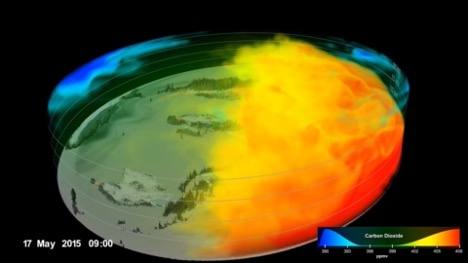

The kinds of representations we rely on to make climate change sensible to the human mind include heat maps, data visualizations, complex computer models trained on vast datasets, and material indexes such as ice-core samples.

It is through these visual forms that we can see across great stretches of time and space, and through which the true nature of climate change comes into view.

[Post-Truth Moment]

To another key issue in the present moment:

How can we photograph a social landscape where spreading uncertainty and misinformation have become key tactics in service of corporate and political interests, such as the stoking of climate denialism by fossil fuel-aligned news outlets and think tanks?

What kinds of images can we create to document the increasing adoption of beliefs that reject facts and evidence, and the growing rates of political polarization along lines of belief? Well, similar to the question of documenting climate change, one might suggest that we could capture photos of the outcomes of these circumstances — circumstances which have been referred to as the ‘post-truth moment’.

For instance, one could take photos of the January 6 Capitol Hill Riots in the United States, which were fueled by false claims of a stolen election. But, would these show us ‘post-truth’? They would show us an outcome of the circumstances described by this term, but it feels incomplete, doesn’t it? Like trying to explain how a gun works by showing a bullet hole.

The true nature of the ‘post-truth moment’ moves through globally spread online networks, across which bonds of belief are forged through curated algorithms, filter bubbles, and echo chambers. It is driven by language that fosters distrust in institutions, spreads uncertainty, and fuels tribal paranoia.

Thus, the kinds of representations we rely on to make sense of the ‘post-truth moment’ include data visualizations, graphs of social network activity, and media and linguistic analysis.

[Challenges to Documentary Practice]

So, as we see, these phenomena — which pose some of the most pressing threats to human life and democratic society — are incredibly difficult to capture through straightforward, traditional documentary images made by a single creator, in the place where the event happened, at the time it happened.

And so, my proposition is that with issues such as these, the future of documentary practice will be increasingly expansive in its materials and approach. This is to say, documentary practice will increasingly embrace materials beyond still images, and it will also increasingly expand beyond the traditional documentary commitments of the invisible author, non-intervention, and non-reflexivity.

[The Future of Documentary]

So, what could this future of expanded documentary look like?

Well, people are already working towards this end.

Perhaps it will openly embrace subjectivity, uncertainty, and artifice to create images that mimic how reality feels in the ‘post-truth moment’ — hyper-individualized and unreliable.

Or perhaps it will involve open-source collaborative investigations using 3D modeling, shaped by vast and widely distributed data and media sources, to produce poly-perspectival texts that speak truth to power.

Or perhaps it will combine official documents and memos with original photographs, vernacular, and archival material, taking up Allan Sekula's call that a ‘truly critical social documentary will frame not just the crime and the trial, but the system of justice and its official myths’.

Expanded documentary practice expands the faculties with which the form can make sense of the world. As we face issues like climate change that increasingly challenge our sensory comprehension, and as our social and political life increasingly takes place in non-physical spaces, expanded documentary practice becomes ever more vital.

It extends documentary’s field of view, enabling it to bring new spaces and phenomena into focus. It helps us to push back against attempts to exploit uncertainty and obscure truth and evidence by those with cynical aims. And perhaps, in this way, it can become a tool to bridge polarized lines of belief and ideology.

Thank you

Good Afternoon.

I wanted to start my talk today with a question:

How do you take a photo of climate change?

Perhaps you would travel to a dried-up riverbed and take a photo. But what would this photograph show you?

I mean, it would capture an outcome of climate change. But this feels somewhat incomplete, right? If we’re talking about photographing climate change as a phenomenon, it’s not an occasional event that happens in sporadic, discrete moments. It’s happening continuously, all around us, often going unnoticed in the present moment. It’s an event that is temporally and spatially spread in a way that often escapes our senses, and in this it challenges the very limits of photographic documentation.

The kinds of representations we rely on to make climate change sensible to the human mind include heat maps, data visualizations, complex computer models trained on vast datasets, and material indexes such as ice-core samples.

It is through these visual forms that we can see across great stretches of time and space, and through which the true nature of climate change comes into view.

[Post-Truth Moment]

To another key issue in the present moment:

How can we photograph a social landscape where spreading uncertainty and misinformation have become key tactics in service of corporate and political interests, such as the stoking of climate denialism by fossil fuel-aligned news outlets and think tanks?

What kinds of images can we create to document the increasing adoption of beliefs that reject facts and evidence, and the growing rates of political polarization along lines of belief? Well, similar to the question of documenting climate change, one might suggest that we could capture photos of the outcomes of these circumstances — circumstances which have been referred to as the ‘post-truth moment’.

For instance, one could take photos of the January 6 Capitol Hill Riots in the United States, which were fueled by false claims of a stolen election. But, would these show us ‘post-truth’? They would show us an outcome of the circumstances described by this term, but it feels incomplete, doesn’t it? Like trying to explain how a gun works by showing a bullet hole.

The true nature of the ‘post-truth moment’ moves through globally spread online networks, across which bonds of belief are forged through curated algorithms, filter bubbles, and echo chambers. It is driven by language that fosters distrust in institutions, spreads uncertainty, and fuels tribal paranoia.

Thus, the kinds of representations we rely on to make sense of the ‘post-truth moment’ include data visualizations, graphs of social network activity, and media and linguistic analysis.

[Challenges to Documentary Practice]

So, as we see, these phenomena — which pose some of the most pressing threats to human life and democratic society — are incredibly difficult to capture through straightforward, traditional documentary images made by a single creator, in the place where the event happened, at the time it happened.

And so, my proposition is that with issues such as these, the future of documentary practice will be increasingly expansive in its materials and approach. This is to say, documentary practice will increasingly embrace materials beyond still images, and it will also increasingly expand beyond the traditional documentary commitments of the invisible author, non-intervention, and non-reflexivity.

[The Future of Documentary]

So, what could this future of expanded documentary look like?

Well, people are already working towards this end.

Perhaps it will openly embrace subjectivity, uncertainty, and artifice to create images that mimic how reality feels in the ‘post-truth moment’ — hyper-individualized and unreliable.

Or perhaps it will involve open-source collaborative investigations using 3D modeling, shaped by vast and widely distributed data and media sources, to produce poly-perspectival texts that speak truth to power.

Or perhaps it will combine official documents and memos with original photographs, vernacular, and archival material, taking up Allan Sekula's call that a ‘truly critical social documentary will frame not just the crime and the trial, but the system of justice and its official myths’.

Expanded documentary practice expands the faculties with which the form can make sense of the world. As we face issues like climate change that increasingly challenge our sensory comprehension, and as our social and political life increasingly takes place in non-physical spaces, expanded documentary practice becomes ever more vital.

It extends documentary’s field of view, enabling it to bring new spaces and phenomena into focus. It helps us to push back against attempts to exploit uncertainty and obscure truth and evidence by those with cynical aims. And perhaps, in this way, it can become a tool to bridge polarized lines of belief and ideology.

Thank you

The Murray Darling Basin.

Source: Dean Lewis

Visualisation of atmospheric CO2.

Source: NASA, Carbon Observatorv-2 satellite.

Mean Global Termperature, 1851 - 2020.

Source: Neil Kaye.

A crowd prepares for Donald Trump’s speech on January 6, 2021.

Source: Bill Clark, Getty Images.

Data visualisation of hashtags on Instagram during the Brexit Referendum, 2016.

Source: Vyacheslav W. Polonski, Oxford Internet Institute.

From Margins of Excess, Max Pinckers.

.

.

Installation views from Forensic Architecture.

Source: Forensic Architecture.

Installation view, Monsanto, Matthieu Asselin.

Source: Matthieu Asselin.